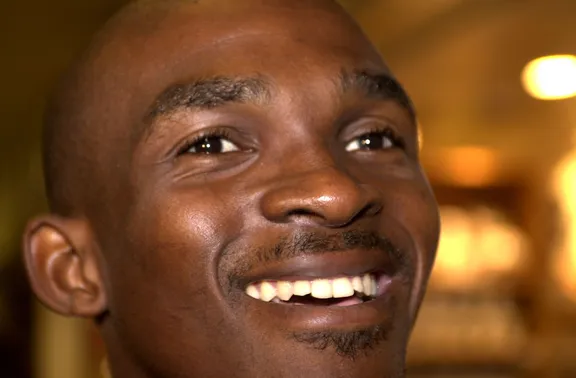

Luck led to Eric Moussambani getting chosen to partake in the 2000 Olympics. He wasn’t well-trained as a swimmer, and a mix-up landed him in a race he wasn’t qualified for. The competitor still gave it his all, and his efforts got him noticed by his country’s government.

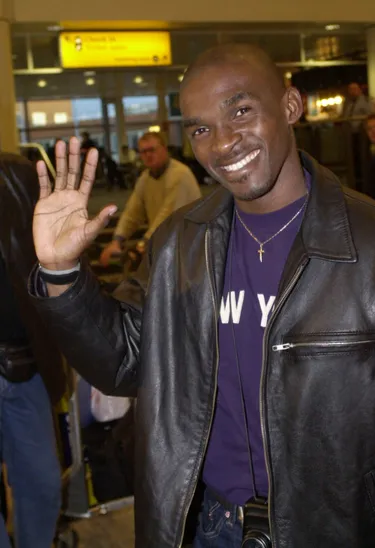

Eric “the Eel” Moussambani arrives at Heathrow Airport to present a prize at the National TV Awards on November 11, 2000, in London | Source: Getty Images

How Moussambani Got Invited as an Olympic Participant despite Not Being a Professional Swimmer?

Moussambani got his Olympic participation invitation through a specific program. The program allows a handful of people who don’t meet the qualifying standards to compete in the Olympics. IOC President Juan Antonio Samaranch promoted the initiative to help the worldwide spread of sports.

The opportunity gave Moussambani the chance to partake in the 2000 Sydney Olympics. The program was also instrumental in giving Eddie “The Eagle” Edwards a chance to compete in the 1988 Calgary Winter Olympics.

Eric “the Eel” Moussambani at Heathrow Airport to present a prize at the sixth National Television Awards on October 10, 2000, in London | Source: Getty Images

Despite being a plasterer at the time, Edwards participated in the ski jump event.

Here’s how Moussambani trained to become an Olympian.

Moussambani’s Journey to Becoming an Olympian

Moussambani once revealed that he started swimming after leaving school. Due to his poor background, he trained at a private hotel’s swimming pool. The pool in Malabo, his hometown, was around 13 meters long. He was only able to use it for the hour it was available from 5 a.m.

Eric Moussambani speaks with AFP while standing next to a 12m long swimming pool, similar to the one he used to train while preparing for the Olympics, at the CHN Flat-Hotel in Malabo on September 12, 2020 | Source: Getty Images

The athlete only managed to train for three hours weekly. To make up for the extra free time he had, he went to the rivers and the sea. Moussambani recalled fishermen trying to guide him on how to swim by telling him how to use his legs.

The star noted, “There was nothing professional about it at all.” After securing his entry into the Olympics, Moussambani started teaching himself how to swim more earnestly since he had no formal experience.

Eric Moussambani speaks with AFP while standing next to a 12m long swimming pool, similar to the one he used to train while preparing for the Olympics, at the CHN Flat-Hotel in Malabo on September 12, 2020 | Source: Getty Images

The athlete managed to nail the basics while training alone but had no one to help him measure his speeds in a 20-meter pool that had no lanes. To make things worse for the competitor, before the Games started, he was wrongly informed that he’d partake in the 50m swimming race, which he trained for.

In the opening ceremony, the star carried his country’s national flag, leading a team of eleven people, including a female swimmer. When he got to Australia, he was shocked to find out that he was expected to swim twice the distance for 100m.

Eric Moussambani carries Equatorial Guinea’s national flag at the Opening Ceremony of the World Swimming Championships in the Marine Messe, Fukuoka, Japan, on July 20, 2001 | Source: Getty Images

It was something he’d never attempted before. Luckily, his rivals, Nigeria’s Karim Bare and Tajikistan’s Farkhod Oripov, had false starts before being “disqualified for their overzealousness.” Moussambani was the only competitor left, and the assumption was that the heat would be canceled and the athlete would proceed to the next round.

But after discussing it, the Olympic authorities decided the swimmer would compete against the clock. His initial goal was to make the qualifying time of one minute and 10 seconds.

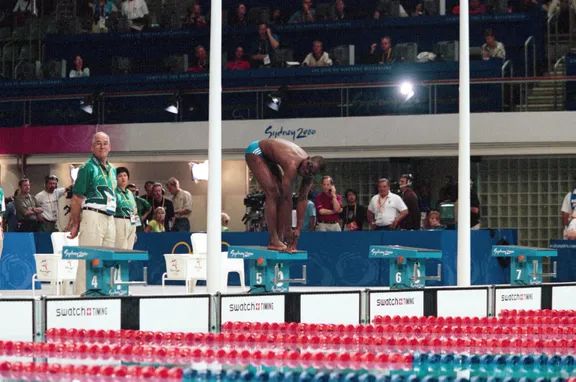

Eric Moussambani during Men’s 100m freestyle heats at the 2000 Summer Olympics, on September 19, 2000, in Sydney, Australia | Source: Getty Images

At age 22, Moussambani dived into the 50m pool and gave it his best shot. When the 17,000 spectators realized the athlete wasn’t a professional swimmer, some of them started laughing. But some people still encouraged the athlete with half-hearted cheers.

Sadly, after reaching the halfway mark in 40.97 seconds, it became obvious that he was in over his head. He’s since revealed what the experience was like.

What Went through His Mind as He Pushed for the Finish Line?

Speaking about the race after he completed it, Moussambani confessed that the last 15 meters of swimming “were very difficult.” He recalled swimming the first 50m “really well,” while focusing his energy on psyching himself to keep pushing until the end.

The athlete knew the world was watching him, including his family, country, and friends. They also served as his motivation to keep going and finish despite being alone in the pool. Moussambani didn’t worry about the timeframe and only focused on completing the race.

While continuing the second half of the race, he suffered after having exerted a lot of energy in the first half. His legs became stiff, and he felt like he wasn’t moving anymore. There was a point while he swam where poolside observers looked anxious as they watched Moussambani struggle.

Ten meters away from the end, officials considered rescuing the athlete when he appeared to sink below as he was ready to give up. But he gave one last effort when he started hearing the crowd shouting, “Go, go, go.”

Their encouragement gave him the strength to finish the one-man race. When he finally touched the wall and finished unopposed, he said to himself, “Oh, I’ve done it.” Speaking about the support he got, the participant said he wished “to send hugs and kisses to the crowd.”

When he returned to his room at the athletes’ Olympic Village, he was surprised to see a sign on the door that read, “Home of Eric the Swimmer.” Moussambani made history as the first swimmer from Equatorial Guinea to compete internationally in the 100m freestyle.

He said, “I was so happy with that achievement, even if my time of 1:52 was not very good.” The star believes the Olympic spirit is “all about taking part,” that and strength is what made him famous.

His time was over the Olympic record, with statisticians noting that it was around 30 seconds slower than Hungary’s Arnold Guttmann. In 1986, Guttmann won Athens’ 100-meter final in open water with a slower time than Moussambani.

The Equatorial Guinean’s time was over seven seconds slower than the 200-meter world record made earlier by Pieter van den Hoogenband. Moussambani admitted that he didn’t want to swim 100 meters because he thought it was too much, but his coach urged him to do it anyway. His efforts earned him fame.

Instant Fame

After finishing his one-man race, Moussambani got surprised with a standing ovation from the audience. Despite not winning, he was also congratulated by the people around the pool. Without his knowledge, that was the moment that placed him in the spotlight.

The world wanted to know more about him, and he suddenly started seeing himself and his race on worldwide television stations like CNN and others. His autograph was also in high demand at the Olympic Village.

He recalled, “I also gave a lot of interviews and the whole thing totally changed my life.” His performance earned him the media nickname “Eric the Eel.” Moussambani hoped to swim again at the 2004 Olympics, but his dream never came true. Yet, he eventually got a significant role.

Reaching New Heights

In March 2012, Moussambani’s appointment as the new swimming coach for Equatorial Guinea got confirmed by the National Swimming Federation (FINA) and the Olympic Committee of Equatorial Guinea (COGE). The decision was made during a meeting at Malabo’s Olympic pool.

The Federation’s first and second vice presidents, Severino Salas Marques and Antonio Andomo Bindang, presented Moussambani with the appointment. He prepared and led the national team that participated in the 2012 London Olympic Games.

Before getting his new role, the swimmer rejected training opportunities offered by international centers. He worked for an oil company in his hometown. But his fame led to invites from television shows and events, and in 2012, his country’s government’s website still received requests for interviews with him.